Brands, advertisers and innovators often think of themselves as operating within a landscape made up of their product or category. Like residents of a physical landscape, they constantly assess changes in its makeup and inhabitants: watching for new generations or new regions appearing over the horizon, checking for earth tremors in shifting political or economic priorities, and retaining relevance by adjusting responsively.

Like this, a fast food brand might keep its cool by introducing some Gen Z nihilism to its communications, or a retailer amp up its e-commerce presence for the Chinese market. This ‘vigilant landscape’ model can make a brand feel flexible and welcoming. If it’s done well enough, it can even make a brand like Levi’s, Microsoft or McDonalds feel timeless, like a part of culture that ‘stays relevant’ by being ever-present, offering something for almost everyone.

But what this model forgets is that new audiences don’t just enter the landscapes of category and product: they create them.

Take beauty. Ten years ago, it would have been hard to predict today’s huge audience of beauty consumers who haven’t experienced ageing, aren’t necessarily looking to solve problems, and see skincare as affirmative self-care. But now, brands from Lush to Kinship are thriving within the fresh category of recreational skincare.

By looking at Glossier’s alignment with the category, we can see how a willingness to become whatever’s wanted – to start afresh where the market’s needs are – make a brand feel as though it truly belongs to its audience.

Image credit: Glossier

Emily Weiss famously kicked off the Glossier brand by soliciting the opinions of her Into the Gloss blog readers. Ideas for the most relevant products came from actual potential customers, in a now-established co-creation dynamic that’s helped many brands connect with their audiences before their products are even out the door.

But this pre-production focus group wouldn’t have succeeded were it not for the insight behind it: that already-pressurised young women were averse to entering a skincare category centred around transformation and optimisation. Instead, the always-on, constantly photographed Gen Z were looking for ways to feel nourished, un-judged and healthy.

Active listening is an essential step for any brand. But what’s more important is taking the leap of imagining: if my category didn’t exist, would my new market or demographic invent it?

And what might they invent instead?

Glossier claims to ‘create the products you tell us you wish existed’ – and it does, with innovations like viscous conditioning cleanser Milky Jelly. But by bringing in a wave of white packaging, sensory skincare experience and buildable, barely-there coverage, it also offered beauty that felt like time and space to pause.

Many category-shifting brands whose successes are perceived – like the rise of DTC beauty – to be tech-driven, in fact succeed by reimagining categories and products for new audiences.

Monzo, for instance, won the quickest crowd-funding success in history by offering British Millennials a bank built from the ground-up on their own needs and desires. Its app features, while impressive, weren’t anything that Barclays or HSBC couldn’t have done; but spending notifications, budget-tracking, ‘pots’ for putting money aside and a friendly, transparent tone showed that Monzo’s vision of what a bank could be was built around Millennial needs.

Image credit: Monzo

This means that the brand still feels like a part of Millennial culture, while few other banks have managed to transcend functionality for younger users.

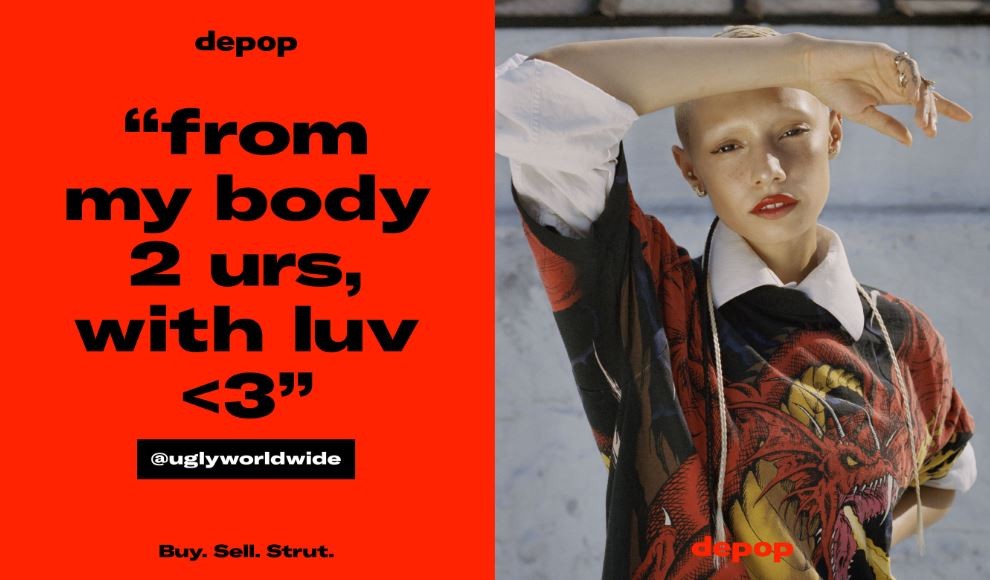

More recently, Depop reimagines what ‘shopping’ might mean to a generation more concerned about sustainability and sociability than any other.

While the site’s offer of easy access to vintage and hard-to-find style are tailor-made for Gen Z, even more important is its rejection of the ideas that a buyer can’t also be a seller, that a laboured-over personal style can’t be monetised without celebrity, and that investment pieces are only for the rich.

Image credit: Depop

Obviously, existing brands are in a different position to new brands created by and with their target audiences. But that doesn’t mean they can’t learn from game-shifters’ ability to ask themselves the question, ‘What would it look like to radically centre my audiences’ actual needs?’

Rather than aiming to protect existing cultural relevance, ambitious brands can reconsider their assumptions – generation by generation and market by market – to stimulate genuine freshness, connection and loyalty. Embracing reinvention allows the needs-based imaginative leaps that help brands strike new audiences as truly relevant.

If you’d like to chat to us about how we can help you centre your strategy around consumer needs, please get in touch.

For more like this straight to your inbox, sign up to our newsletter.