Identity has always been wrapped in clothing. The stitches that pull fabric together also gather the stories and narratives that we communicate to others. Our clothes communicate our place in the world, through implied meanings of class, social status, affiliation to tribes, beliefs and our outlook on the world. Cultural movements are reflected in our garments and can be read as physical manifestation of a communal psyche – what we wear is what we believe in.

Fast fashion and its ready availability has made a trend-led sense of identity available to the whole urban world. People can easily access fashion and whatever identity they want to express. We have found community and a commonality in being trendy, youthful, fashionable, modern and globally aware consumers – a world of opportunity and potential at our well-heeled feet. And yet, fast fashion has also brought with it a culture of hyper consumption and waste. A short-sighted approach by the industry has led to a huge burden on our planet. It is now no news that 60% of clothes find themselves in landfill within a year of being made. In response we have seen a parallel rise of ethical fashion – a bid to mitigate the harm of an industry focussed on disposable turnover. A set of home-grown brands from Asia, such as Grana, Matter, Shokay and Fake Natoo, each in its own way has begun speaking out against the harm of consumerist culture. Their stories revolve around ruthless transparency of cost structures, ethical trade, quality over quantity, preserving traditional fabrics and craft, workmanship, care and a social angle of empowering indigenous communities threatened by fast fashion and other environmental pressures.

Grana pursues quality through being ruthlessly transparent about their production and associated costs and mark-ups, which helps consumers build trust both in terms of garment quality and the integrity of the business. Image credit: Grana

While their efforts are noble, many ethical fashion brands are not accessible to the majority of people. They are expensive, often rely on small scale online sales, don’t entirely solve issues of waste management and, more importantly, their scale of impact just cannot be matched by bigger brands with a huge reach. Beyond these practical problems, there is a real risk of the message behind the action being adopted as an elitist sign of exclusive enlightenment – a club of consumers that are performing status through the consumption of ethical and sustainable fashion, elevating themselves morally above those who do not (cannot) do the same.

Fundamentally we need to see sustainability on the streets rather than the catwalks – a move from the elitist to the democratised.

And we are beginning to see a shift.

Increasingly, there are ‘fast fashion’ brands (a phrase that has rapidly become pejorative) who are taking more responsibility for their environmental impact; a momentous push into the future with innovative materials, recycling plants and circular-loop business models, encouraging people on the street to confront the problems, slow the cycle and adopt more sustainable lifestyles. This isn’t just Fashion Weeks in luxurious venues, this is consumer participation in genuine movements towards sustainability.

Image credit: H&M via Weibo

H&M is struggling with a mountain of unused clothes. But they were also early in adopting upcycled new materials in their product lines. It launched its Conscious Exclusive collection in 2015 featuring eco-friendly clothes constructed with sustainable fabrics made from cellulose fibres in pineapple leaves and other plant-based flexible foams using algae biomass. They showed us how citrus juice by-products could be transformed into silk like fabrics.

The aesthetics of the collection echoes the affinity to nature, emphasizing a certain care and respect in its flowy silhouettes and striking colour palette. H&M explored the theme of the healing power of nature while embracing textile innovation further by pledging to honour a Zero-waste lifestyle. They have moved their efforts on by teaming up with a network of facilities, other brands (such as Danone) to come up with ways to create textiles out of waste.

They have also started urging consumers to become fashion recyclers, sharing their sense of purpose with consumers, making it clear that everyone needs to contribute to the regenerative culture, but still reducing the barriers for consumers to engage.

A model at Reclothing Bank’s fashion show, with make-up marking important dates and numbers on her face. Image credit: Reclothing Bank

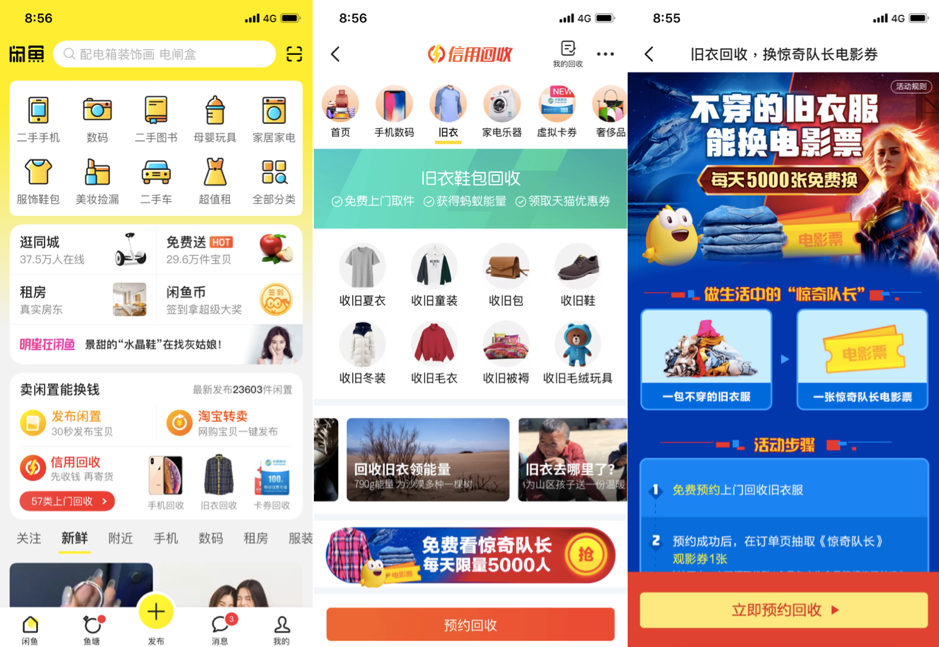

Reclothing Bank, a label from Shanghai, upcycles secondhand clothing in its collections. Zhang Na, the label’s founder, speaks of old clothes as vessels containing traces of people’s lives, as objects that inspire reflection. She introduced her collection through contemporary social theatre, portraying life in Modern China with the help of Shanghainese families, models, and actors. The label earned itself a cult following, demonstrating the benefits of aligning brand story with the narratives within a culture. And it’s not just high-end labels rewriting the cultural narratives around second hand. High streets in larger cities are no strangers to upcycled and vintage fashion, such as Pawnstars in Shanghai or Vintage Caravan in Beijing. Clothing swaps and second hand clothes stores are visible and popular parts of consumers’ lives. Beyond small scale entrepreneurs keen to address sustainability, China is also seeing a rise in huge scale ecommerce platforms such as Xian Yu.

Image credit: Xian Yu 闲鱼

Xian Yu, Alibaba’s second hand platform, has seen 8,500 tonnes of clothes given new homes since it launched in March 2018. Beyond the significance of diverting 24 million garments from landfill, users of Xian Yu are given ‘green power points’ on affiliate app Ant Financial as a reward for shopping, but can also gather them through opting in to schemes such as paperless billing and taking public transport – encouraging wider lifestyle change. These points are then translated into anti-desertification efforts through planting trees. Since 2016, when Ant Financial launched, 400 million users have activated accounts.

This is not a small movement – this is not consumer indifference.

The urgent rise of a conscience in the fashion industry reflects the changing consumer culture evident in Asia and across the world. It is clear that as we construct our identities in the future that sustainability will feature significantly. Consumers want to contribute, to be forces for good, and to look and feel damn good doing it. The sustainable future that more and more voices are clamouring for will change our relationship to the clothes and shoes we wear – our beliefs are changing and how we choose to be seen and what we wish to be associated with is changing too. People have already started opting for brands that deliver on conscious production. The remodelling and refashioning of clothes is the next creative pursuit and the fashion industry is talking about creating longer standing relationships with owned clothes rather than having a disposable approach.

Global brands are making considerable strides into technology and infrastructure that produces greener products at scale. Brand owners and marketeers have a responsibility to help consumers truly understand the connection between their choices and the impact on the environment. Brands can do more than just talking about their sustainability efforts in isolation (as it might come across as too indulgent), but it’s evidently possible to weave that effort into the brand story. Consumers are willing to be taken on a journey towards a more desirable future, so why not take them there now?

Image credit: Nuan, Fake Natoo