In the midst of fourth wave feminism, particularly in the United States, women are looking stronger than ever. They are visually represented with more bulk, more muscle, or just more curves as a way of taking up space and asserting their place in the world. Culturally-savvy brands and icons push these cues of female power to propagate body confidence, and emotional and psychological confidence. The contemporary woman is not afraid to make room for herself and these semiotic cues of strength come from the wrought body itself. Power dressing isn’t attained with shoulder pads but must be worked at, laboured over, and celebrated through ongoing rituals like exercise and positive affirmation that continually prove that a woman’s body will not stand in her way. She must lean in, earn her right in the workplace, and in culture, with ongoing exertion, and by making herself visible.

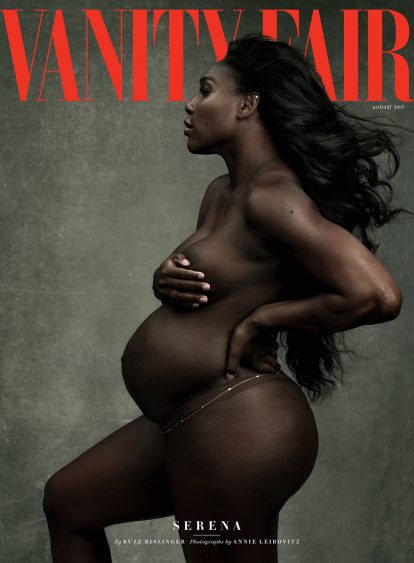

Vanity Fair evinces not just her stellar physique and sculpted muscles but also her unequivocal femininity. We see her naked: the raw flesh behind the tennis championships, the body that won the Australian Open while in the most precarious first trimester known for nausea and miscarriage. Annie Leibovitz’s portrayal revealed her real or unfiltered female body that is no longer just an athlete’s. Overnight, Williams went from competitive athlete to Woman. Her dark skin moulds to muscles, glands, and yes, new life, enveloping her strength in seductive copper and curves with hair loose, long, and shiny. She is more than a woman; she’s a goddess emerging from a hard shell.

Shifting from the spotlight of Black Excellence, Williams was, until recently, a hard graft body, strong and able – a champion. In 2014, in Citizen: An American Lyric, Claudia Rankine calls her “the best female tennis player of all time” after revealing how a black body becomes a space of invisibility. Later, in “The Meaning of Serena Williams”, Rankine further positions Williams as a contemporary cultural icon— a black woman who unapologetically takes up space. Her body and body language betray her unabashed penchant for winning, and form a powerful example of how a black woman leads the way for all women. Like Beyoncé, Williams is an icon of African American strength and leadership but is also a leader who transcends race altogether, becoming a symbol of female power. If we adopt her cues, her body attitude and language, we are on our way to winning in life. Be strong, be powerful, and make it known.

Her win at the Australian Open certainly suggests a superhuman, the very cinematic play of a woman who does not let her body stand in her way, let alone fall prey to the fear of miscarriage. The outdated concept and misnomer “miscarry” suggests an incapacity, a lack of abundance and a woman who is incapable. Williams dispels this volatility, apparently unafraid and even more tenacious than usual – continuing to embody and herald the female body as absolutely heroic.

In 1992, Demi Moore’s Vanity Fair cover (that Williams’ mimicked) shockingly equated pregnancy with Hollywood glamour and since then, the pregnant belly has been revealed, embellished, photographed, and is confidently proliferating throughout popular culture. With Beyoncé’s recent unveilings, it is an exciting time for a woman in the U.S. to be pregnant. Fertility is not just a private celebration but a cultural commodity. While many celebrities bare their bellies, few images catapult them to goddess status, demonstrating that “excellence” is a prerequisite for successful pregnant disrobing. Not any celebrity can get away with glorifying something so private.

Over the years, the pregnant belly has gone from decently cloaked to naked – without the restrictions of immobility, wedding vows, fidelity or other excuses to sequester or shame the occurrence. Although as recently as 2014, Karl Lagerfeld still shocked the fashion world by sending a pregnant bride down the runway – a bold sign of dismantling America’s Puritan ideals and persistent tension over the female body. This year’s photoshoots with Beyoncé and Williams reveal an outward and blatant veneration of female fertility. They aren’t just female nudes. While they definitely echo sex – Beyoncé’s more than Williams’ – they are celebrations of a power that is distinctly female. Power dressing isn’t about adding armour but about embodying strength and ultimate dominion.

Dressing the female body is still fraught with tension, especially when it comes to coding power. In a recent move toward proper decorum, Congress announced that women are banned from entering the Speaker’s Lobby in sleeveless dresses, sparking another debate around dressing in a so-called man’s world and how to make the female body more asexual. Whereas in February 2017, Hadley Freeman hinted that feminisation was a palatable pill to swallow for leading right-wing political female figures. She observes how all the women on Fox News look and dress alike, citing the Republican preference for long, bottle-blonde hair as seen in Kellyanne Conway, Ann Coulter, and Ivanka Trump. Hadley rightly notes, “American right-wing women all dress exactly the same, which is to say, mainstream feminine – dresses, not trousers; heels, not flats; no interesting cuts, just body-skimming, cleavage-hinting, not-scaring-the-horses tedium.” These women stand in shocking contrast to the abundant, nude black woman. The Ivanka Trumps barely skim the surface of residual models of female power and just because they may be in the spotlight, it doesn’t mean their sartorial cues are exemplars of power. Rather they represent a re-emergence of the traditional domestication of women.

Hadley recalls another dated trope of power dressing, noting that “some left-wing women wear pantsuits (remember those?),” a uniform notoriously donned by Hilary Clinton during her presidential campaign and for which she was continually criticised. Evidently, it was not the wardrobe choice of a winner. According to her Twitter account, she is a self-proclaimed “pantsuit aficionado”, a cute and perplexing announcement for a leading female politician. Likewise, her wardrobe was a compromise: the most available and immediate tool to code female power and a safe, unthreatening, option for the first female presidential candidate. This physical adaption of corporate America was a concession for the most patriarchal office in America but in light of more poignant options, the pantsuit worked against her, failing as male camouflage while simultaneously obscuring her gender. In 2007, Clinton’s cleavage made the Washington Post, but she since eschews sexuality, even modifying dresses so as to demonstrate her own inner power. Is it possible that in striving for equality and even excellence, Clinton actually hid one of her most powerful assets: her femininity?

Michelle Obama’s bare arms are partly responsible for bringing physical female strength into the mainstream when she first took office as First Lady. Even after leaving the White House, her shoulder-bearing, off duty tops reveal body contours that seduce fans who idolise her femininity and that likewise reconsider if the cues of female power don’t include a little more skin than we expected. Dressing for a man’s world is a dangling question – something Michelle never did, whereas Ivanka is very much the legacy and daughter of a male president. More emergent cues of female power suggest dressing for a woman’s world – or at least a less binary one. In recoding power, women must find their own limits and dress code within culture.

Both Beyoncé and Williams have been spotlighted for flaunting the pregnant body and perhaps overexposing motherhood as nothing more than a glossy image. One critic, Robin Givhan, wrote in the Washington Post that, “Like so much else in life today, pregnancy must be performed.” While there is a stage mom on steroids aspect, the images defiantly turn the page on the emaciated body of not too long ago, the damsel who is too thin to menstruate à la Kate Moss or Fiona Apple.

Fertility is a rooted and mythological cue of female power, enlivened today even in the crimson robes and ceremonies found in the TV adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s dystopic The Handmaid’s Tale. Within the cultural context of America, these recent photo spreads politically challenge the still unsettling discussion around who owns a woman’s body, let alone how to dress it. As excellent women take up space, love their bodies, lean in, and shape our culture, they restructure it. A big belly that is both naked and pregnant is part of that foundation. As perfectly posed and on brand as those images are, they are still raw and unfiltered. Exposing those mysterious mounds invokes abundance, goddess worship, and paganism – fertility that’s a deified and prized resource. Recoding power isn’t just about taking up space but unearthing inner strength and life within.

— Hannah Hoel